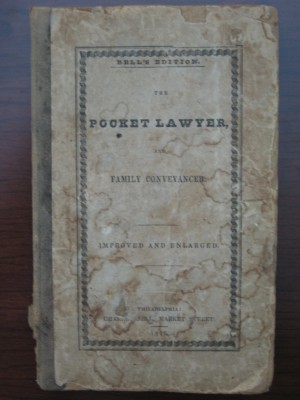

Well, one of my 2014 resolutions is to find a better balance between writing blogs (which I’ve sorely neglected of late) and my other online and published work. As such, I’ve decided to embrace inspiration as it comes. The other day I found a charming–at least to me–book called The Pocket Lawyer and Family Conveyancer, this edition published in Philadelphia in 1845 by Charles Bell of Market Street. The author, identified only as a “gentleman of the Bar”, produced what was essentially a compendium of forms related to common legal transactions for laypeople, not unlike the ‘make your own will’ packages one can acquire today. Since my assumptions about what might be found in a book of this period differed somewhat from what was actually included, I thought it might be interesting to profile some of the content.

Most of the documents, not surprisingly, were related to financial and real property transactions that are still (in modified form) used today, such as IOUs, land deeds, and the like. Some, however, clearly reflect the nature of everyday life in the 1840s. One such document, clearly useful in a largely pre-industrial society, was an indenture of apprenticeship: ASSIGNMENT OF AN APPRENTICE. Know all Men by these Presents, That I, the within named Jacob Knox, for divers good causes and considerations, have assigned and set over, and by these presents as far as I lawfully may or can do, assign and set over the within Indenture, and the Apprentice therein named, unto Jeremiah Miller, his heirs and assigns. He and they performing all and singular the covenants therein contained on my part and behalf to be done, kept, and performed, and indemnifying me for the same. WITNESS my hand and seal, the twenty-first day of August, One thousand eight hundred and thirty-four.

Related to that, a form for assigning (transferring) an apprentice to another employer was also included. Other forms, such as mortgage documents and property leases, are mere wisps of what they would be today.

Entrepreneurs of the period might opt to open a “publick house” or the like. In order to do so, one generally had to petition the local court, and in Pennsylvania also to include a recommendation from “twelve respectable inhabitants” of one’s county. Here is one such template:

PETITION FOR LICENCE TO TAVERN-KEEPERS. To the Honourable the Judges of the Court of Common Pleas of Berks county, now composing and holding a Court of General Quarter Sessions of the Peace, in and for said county, of September Term, 1834. The petition of George Potts, of the borough of Reading, in the county of Berks, respectfully sheweth: That your petitioner is desirous of keeping a public house or tavern, in the house, [here describe the situation, &c.,] that he has provided himself with necessaries for the convenience and accommodation of travellers and strangers. He therefore prays your honours to grant him a license to keep a house of public entertainment in said house. And he will pray, &c. GEORGE POTTS. WE the subscribers, do certify that George Potts, the above applicant, is of good repute for honesty and temperance, and is well provided with house-room and conveniences for the lodging and accommodation of strangers and travellers.

But perhaps your troubles were–ahem–a little less pedestrian–such as want of a road? In that case: PETITION FOR LAYING OUT A ROAD. To the Honourable the Judges of the Court of Common Pleas of Juniata county, now composing a Court of Quarter Sessions of the Peace, in and for said county. The Petition of divers inhabitants of the township of _____ in said county, humbly sheweth: That your petitioners labour under great inconveniences for want of a road of highway to lead from _____ to _____ Your petitioners therefore humbly pray the Court to appoint proper persons to view and lay out the same, according to law. And they will pray &c.

And if the problem was not want of a road, but the opposite, then conversely one would want a PETITION FOR REVIEW OF A ROAD, in which the petitioners humbly sheweth: “That a road has been lately laid out, by order of the Court, from ….&c. which road, if confirmed by the Court, will be very injurious to your petitioners, and burthensome to the inhabitants of the township through which the same runs. Your petitioners therefore pray your honours to appoint proper persons to review the said road, and parts adjacent, and make report to the Court according to law.”

Married women’s property rights are reflected in the “release of dower” document for a widow–the sum she was accorded by law or her late husband’s will to provide for her after his death–in one such document. In exchange for a sum of money from her son she “doth fully and absolutely grant, remise, release, and for ever quit-claim…all the dower and thirds, right and title of dower and thirds, and all the other right, title, interest, claim, and demand whatsoever, in law and equity….”

Well, it’s just a small window into the type of legal transactions that were probably common to many in the middle class, but hopefully still interesting to fans of legal history!

Hi–interesting–looks like people were always trying to save on lawyers bills! Anywya, hope you get back in the habit of writing your blog more often, in addition to your legal facts. All best, GH

I am glad to see that you are writing the blog again and also your other postings. nice to read it!

thank you!